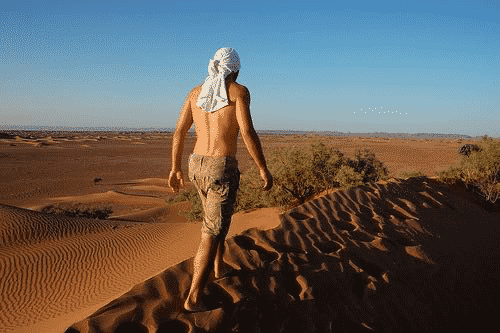

Curiosity, and a Walk Through the Desert

I’ve been feeling damn frustrated since I got back from South America. Since I returned, I’ve been exploring different technological landscapes, looking to see which area draws me in.

From May through July, I spent a lot of my time building crappy prototypes. And trying to come up with new ideas. And I didn’t like any of them.

Organic interest

Either the ideas were just plain bad, or weren’t sustainably interesting to me. There were quite a few that would work and make somebody a lot of money, but not me—I was just the wrong person to deliver on that idea. I mean, if I couldn’t get myself interested in working on something for more than two weeks, how could I possibly build it into something real and interesting for other people? Nonstarter.

There has to be a basis of organic interest.

The (wrong) question?

By July, I felt very frustrated by the lack of progress and the desire to have a direction to run in. So I started asking other entrepreneurs, “what do you do in this situation? what do you do when you’re trying to come up with something interesting and hating everything you’re coming up with?”

This was a mental walk through the desert. This became The Question.

The Question generated a lot of answers. Mostly useless answers.

Why? Because The Question was actually The Wrong Question.

In July, I was up in San Francisco and had lunch with Mat Johnson, a very smart guy who works on distribution with 500 Startups portfolio companies. Just like everyone else, Mat got hit with The (soon to be known as) Wrong Question. His response? “Yeah, that’s not going to work. You’re forcing it.”

Okay. So, what would? His advice:

I wish I could give you a formula for this, but as far as I know there isn’t one.

The only approach I think has a decent chance of working is just to follow your curiosity and see where it leads you.

As soon as I heard that, I knew it was true. Nonetheless, what I should do didn’t occur to me for awhile.

I took stock of all the different areas I’d looked at in the last six months. All the prototypes, white papers, use cases, everything. What I quickly realized was that all the things that I’d actually thought were interesting, that I thought were neat or cool—as opposed to what I thought I should be interested in—what did these things have something in common?

And that something was the fact that they all involved turning gobs of data into useful information. (Information != data.)

These were use cases such as:

- automatically detecting and preventing e-commerce fraud by using machine learning

- making weather satellites adapt their scanning based on realtime feeds from ground sensors

- predicting which uber-expensive piece of manufacturing equipment most likely to fail next

These are somewhat prosaic on the surface, but actually fascinating in terms of how these results are accomplished. I’m hooked—this big data stuff is thrilling.

New ground

The ridiculous quantities of data we are generating every day are beyond anything we’ve ever encountered in human history. The volume, velocity, and variety of the data we’re generating is so extreme that the tools to handle it are literally being invented as we go.

And I believe in this data. I believe in the latent power in data to make the world a better place and to give people delight and value and help in ways that we can’t even imagine yet.

And so what I realized is that my answer to The Question—big data—has been sitting right in front of me all along. Following my curiosity made me realize that this was the area I really want to explore, and narrowed an overwhelming world of possibility into a concrete direction that I can walk in and work on (lots in the works that I hope to go public with soon).

Where will your curiosity take you? Follow it.

(Photo credit: Sylvain Bourdos)