Understanding the Internet: How Messages Flow Through TCP Sockets

One of the questions that has been coming up a lot lately as many people are building with Akka.Remote is this:

How big of a message can I send over the network?

I’ve been asked about this four or five times this week alone, so it’s time to put out a blog post and stop re-writing the answer. This is a great question to cover, as it starts to reveal more about what is going on under the hood with Akka.Remote and the networking layer.

Up until I worked on Akka.NET, I honestly hadn’t thought much about the networking layer and so this was a fun question for me to dig into and research.

When does this come up?

This comes up all the time when people have large chunks of data that they need to transmit and process. I’ve been asked about this lately in the context of doing big ETL jobs, running calculations on lab data, web scraping, for video processing, and more. People asking about sending files that range anywhere from 20MB to 5GB.

All of these contexts involve large amounts of data that need to be processed, but no clear way to link that up with the distributed processing capabilities that Akka.NET provides.

So what’s a developer to do?

Here’s the first answer people try: “network-shmetwork! JUST SEND IT!”

Why this is a bad idea

This is basically what that does to the network:

That is a python trying to eat an entire pig. Ewwwww. Gross.

If it could feel, that’s how the network would feel about our large messages.

What else do people try to do? Here are some of the common approaches I’ve seen:

- crank up the

maximum-frame-sizevalue (e.g. to 100MB) - crank up the send/receive buffer size

- massively increase the timeout threshold for connections

None of these approaches work. Why? The short answer is that computers (and TCP) have an easier time processing many small messages than a few large ones.

But to really understand, we have to go on a bit of a trip and revisit how TCP sockets work.

We begin our journey with this question…

Imagine you are the read side of a byte stream: I send a never-ending stream of bytes at you.

How do you get anything useful out of that stream?

Answering this question–and starting from the perspective of the receiver–is critical. Let’s see why.

Messages & streams

As developers, we think in terms of messages: “create user”, “debit account”, “deliver result”, and so on. This is how we model our applications, which is great… except that networks don’t think in terms of messages! Networks think in terms of data flows.

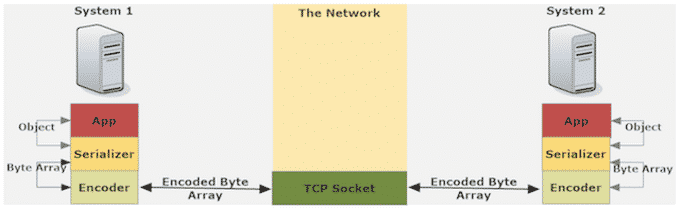

At a high-level, here’s the process of sending data between applications over the network:

- Application wants to send an object (the “message” in app parlance) over the network.

- Object is given to a Serializer, which has the job of representing that entire object as an array of bytes.

- Serialized object string is passed to an Encoder.

- Encoder appends delimiter / header / fixed-width information to the byte array. This is information that the decoder on the other end of the network needs to pluck this specific array of bytes out from the larger, ongoing stream of bytes it’s receiving which contain other messages.

- Byte array is written to the outbound stream in the socket.

- Process is reversed in the receiving application to convert from byte array to usable object.

Here’s what that looks like:

What does this process assume? Offhand, I can see two core assumptions:

- The sender is able to serialize a given object into bytes, and the receiver can deserialize those bytes into an object equivalent to the original. We’ll call this the “equivalent serialization assumption.”

- The sender can encode the serialized object for transmission, and the receiver can identify that byte array within its inbound stream and convert said encoded byte array back into an equivalent serialized object. We’ll call this the “equivalent encoding assumption.”

Essentially, we assume each side of the system “speaks the same language.” If you’ve ever heard the term “wire format,” this is what is meant by it: the serialization + encoding that must be understood by both ends of a connection. Together, our two assumptions add up to “we’re assuming both ends of the connection use the same wire format.”

Serialization is more complicated and difficult than encoding, and it’s beyond the scope of this post. We’ll be spending our time with the step closest to the network: Encoding.

How TCP sockets think

As outlined beautifully by Stephen Cleary, this is the fundamental disconnect that causes issues for developers when considering the network: we think in messages, but TCP sockets think in streams.

Let’s repeat that, because it’s the basis of everything that follows:

Applications work with messages. TCP sockets work with streams.

These “streams” are bidirectional byte streams. That is, a socket can send an ongoing stream of bytes(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byte) in both directions. Each socket has an incoming stream, and an outgoing stream. The fun side of a socket is the receiving side, which faces the dilemma I posed earlier: if we have a continual river of bytes flowing past us, how do we get EXACTLY the same string that went in on the sender side back out on receiving side?

This is achieved through a process called “message framing.”

What is message framing?

Message framing is the encoding process by which we package up our serialized objects before we hand them off to TCP for network transmission.

How does message framing work?

For the receiver to get a usable message frame out of a stream of bytes, it must know one key piece of information: how long the frame is.

For example, if we know that the next frame is 5 bytes long, we just need to capture the next 5 bytes, and bam! We’ve got our frame back, ready to be converted from bytes to a string and then deserialized.

Generally, there are three ways to encode frames: length-frame encoding, delimiter-based encoding, and fixed-length encoding.

Wait, but what about packets?

TL;DR; you can mess with packet sizes but you probably shouldn’t.

Max packet sizes are often out of your control, and are affected by the various components of the network (switches, routers, etc.). If your message frames are bigger than the max packet sizes allowed, TCP will subdivide your frames into packets and put the frame back together again on the other end of the socket from the packet sequence.

You have the ability to affect packet sizes within certain ranges, but you can’t make them arbitrarily large and it’s often dangerous to mess with them.

Length-frame encoding

How do we know the length of the frame in this encoding? We make the first byte of our frame state the length.

Length-frame encoding works by declaring the length of the frame, and then following that immediately with the bytes of the frame itself. This method places markers in the stream saying “next frame is N bytes”, so the receiver can see that and then know how many of the next bytes make up this frame. The format and length of the length-prefix must be explicit and identical on both sides of the connection (e.g. 4-byte signed little-endian)

Length-frame encoding is the most commonly used message framing protocol.

Advantages:

- Flexible encoding that can handle large or small message frames

Disadvantages:

- Have to manage allocating buffers based on the length-prefix

- Some systems will always hold memory for the largest buffer they’ve seen, resulting in wasted memory.

Here’s what length-frame encoding and decoding looks like:

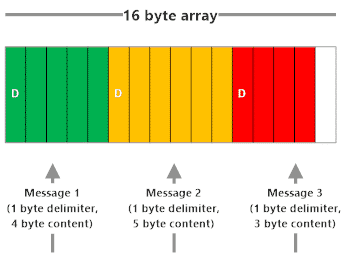

Delimiter-based encoding

How do we know the length of the frame in this encoding? We put a delimiter between each frame. This delimiter needs to be something that won’t show up in the actual message frame, like a null terminator in C

Advantages:

- Flexible encoding that can handle large or small message frames

Disadvantages:

- Easier to mess up. Have to deal with escaping / unescaping delimiters.

- The receiving side never knows in advance how big a frame is, and has to grow a receiving buffer as needed.

- God help you if somehow you have delimiters show up in your message where you don’t intend them.

Here’s what delimiter-based encoding looks like:

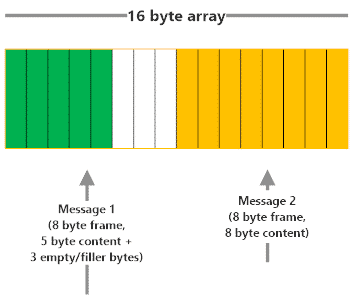

Fixed-length encoding

How do we know the length of the frame in this encoding? This one is simple, all frames are the same length!

Advantages:

- Simple to think about.

Disadvantages:

- Inefficient. We often have to “fill up” frames when what we want to send is shorter than the fixed-length frame.

- Inflexible. Doesn’t adapt to different message sizes and can forces you into choosing either wasted memory with small fixed-length frames, or forces you to take on the added complexity of stitching together multiple frames that could be represented as one frame under a different encoding.

Here’s what fixed-length encoding looks like:

What TCP sockets can & can’t handle

TCP sockets don’t support arbitrarily large packet sizes. In answer to the question, “how large of a packet can I send over TCP?,” there are varying answers ranging from 1400 bytes to 65kB. But that’s actually irrelevant here: regardless of what the max packet size really is, it is definitely much smaller than the amount of data you want to move.

Further, some network transports have built-in maximum frame sizes. For example, if you try to write a 100MB datagram to a UDP socket, the OS will just throw an error immediately and never even try to send the message.

When you try to send 100MB over a TCP socket, TCP will just see that it has (some very large) number of packets N to deliver, sequence, and confirm. As soon as the receiving OS starts getting ordered packets, it will begin paging them into a buffer for the encoder to decode. But here’s the thing: this blocks the socket. TCP, and the encoder, have to just sit there waiting for the rest of the gigantic message to arrive over the network.

Assume you want to send 100MB over the network, and a 10kB packet size. That’s 10,000 packets that have to be sent over the network, in sequence, and have their delivery confirmed by the receiver. Now, it’s true that TCP doesn’t have to wait for all 10,000 packets to arrive before it can begin sending bytes into your application. But if, let’s say, TCP has only received the first 400 sequenced packets so far, then the socket will be blocked from receiving all other messages until it receives the remaining 9,600 packets and sequences them.

Guess what? Not only are you introducing a blocking and likely-to-cause-errors design, if your node is part of a cluster, it probably just started failing heartbeats to its peers! They now think it’s down when it’s not, and you have a split-brain scenario. And the processing of every other message flowing to this node now is now delayed.

Aside: this is why other network protocols, like FTP, exist. For example, FTP handles the buffering of large incoming data more efficiently by incrementally flushing received data to disk and freeing up memory for more network bytes, because it knows it’s dealing with files and thus can handle them in a specialized way. TCP is a more low-level, generalized protocol and can’t make that type of tradeoff.

It’s much easier for TCP to transmit and reconstitute many small objects than to do so with a few massive objects.

Also, in the case of network failures–which are inevitable–it’s much, much, MUCH better to have small messages. Retrying small messages is cheap and easy. Retrying 100MB at once is not. As you increase your messages sizes, you multiply the costs of every single, inevitable network failure.

What does this all add up to?

Let’s review what we’ve learned so far, from a TCP point of view:

- Your objects get serialized and then encoded into message frames.

- Each message frame will be organized into sequenced TCP packets for transport. How this happens, and the packet sizes, are generally below the level you control as a developer. You probably shouldn’t mess with this.

- Packets are sent over the network and the receiving OS can begin paging the sequenced bytes into the application for decoding, but the socket is blocked until the entire packet sequence is delivered or fails.

- This slows down the entire system, and will also cause partitions and split-brain scenarios if you’re working in a clustered environment due to missed heartbeats.

Coming full circle, what does this all add up to in the context of sending a large message over the network?

When working with TCP, it’s your responsibility as a developer to manage the size of objects you transmit over the network.

Forcing the OS and the network to cut up massive objects for you leads to errors, brittle systems, lots of blocking, and a much less performant app.

This post originally appeared on the Petabridge blog.